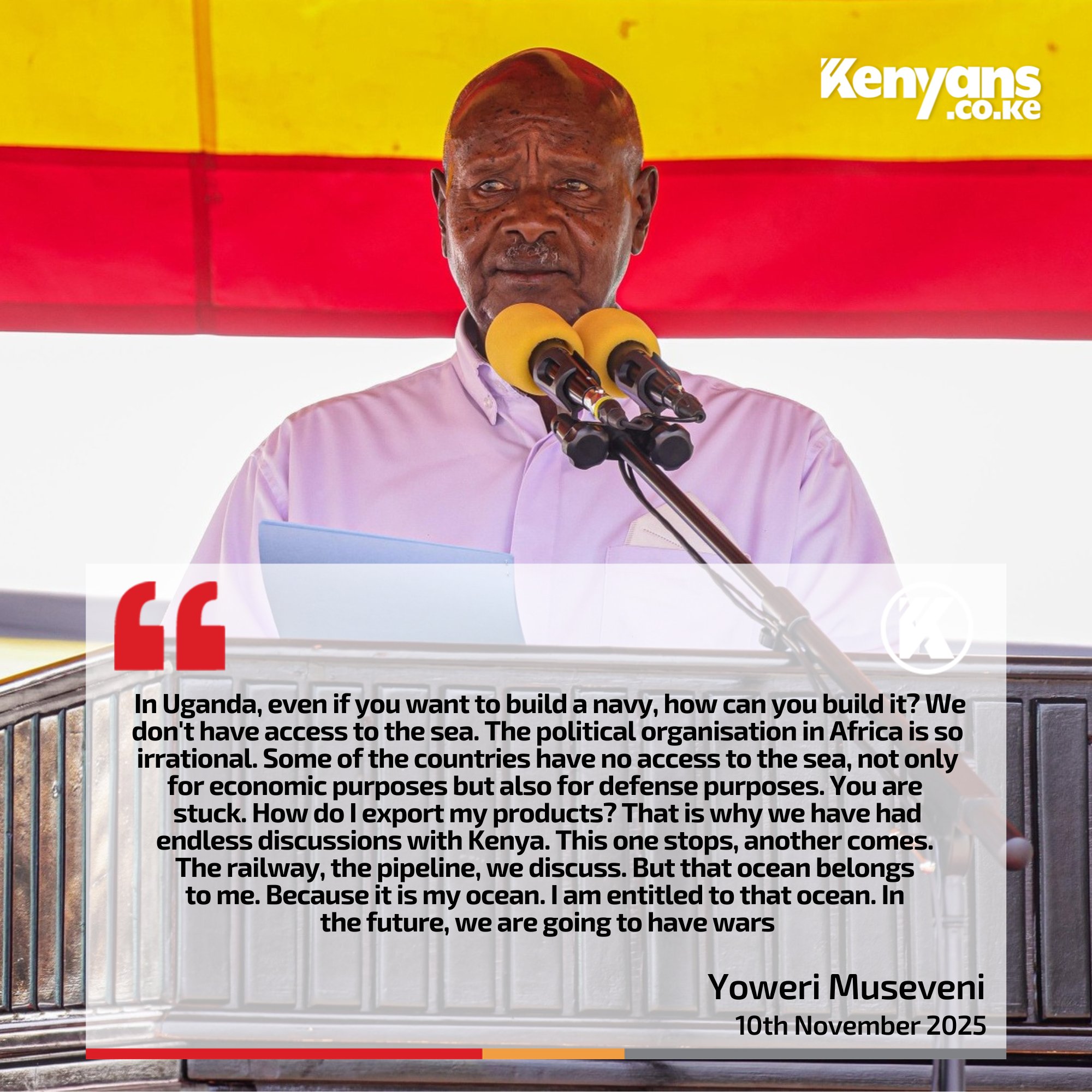

In a recent statement that sparked regional debate, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni declared, “That ocean belongs to me. Because it is my ocean. I am entitled to that ocean. In the future, we are going to have wars.” While many observers initially dismissed the remark as rhetorical bravado, it reflects a deeper sentiment of African nations reasserting their maritime and resource sovereignty amid a changing geopolitical landscape.

Museveni’s words, though provocative, tap into a legitimate historical and developmental grievance shared by several landlocked African states. Uganda, despite its access to major inland water bodies like Lake Victoria, remains economically constrained by reliance on coastal neighbors for trade routes and maritime access. The president’s statement, therefore, symbolizes a demand for equitable access and benefit-sharing from regional seas and maritime resources, which are often dominated by former colonial or global powers.

Ethiopia’s Case: A Different but Related Struggle

While Ethiopia’s maritime claim differs substantially from Uganda’s, both are rooted in the question of historical justice and national survival. Ethiopia once possessed a coastline along the Red Sea through the province of Eritrea, but lost direct sea access following Eritrea’s independence in 1993. For Ethiopia, this separation represented not merely a political division, but the loss of a historic maritime identity that had linked its civilization to global trade routes for centuries.

Unlike Museveni’s generalized claim, Ethiopia’s pursuit of sea access — notably through diplomatic engagement and port agreements with Djibouti, Somaliland, and other coastal states — is based on historical continuity and legitimate economic necessity. Addis Ababa has consistently emphasized peaceful negotiation, economic partnership, and regional integration rather than confrontation.

A Shared African Dilemma

Both Uganda’s and Ethiopia’s positions expose a wider African dilemma: the structural legacy of colonial borders that cut off states from their natural maritime and trade networks. More than 15 African countries remain landlocked, yet many contribute significantly to regional maritime economies through trade, tourism, and infrastructure.

Museveni’s bold tone, therefore, resonates as a call for a new African conversation about maritime justice — one that demands fairer regional cooperation, shared infrastructure, and mutual recognition of historical grievances. Ethiopia’s case, grounded in diplomacy and historical legitimacy, provides a model of constructive engagement for other inland nations seeking maritime access without igniting new conflicts.

HornCurrent View

President Museveni’s assertion should not be dismissed as mere rhetoric. It is an expression of Africa’s reawakening to questions of sovereignty, geography, and economic destiny. While Uganda’s situation is distinct, his sentiment echoes the legitimate aspirations of Ethiopia, which continues to seek rightful access to the sea that history separated by political accident rather than by choice.

As Africa’s geopolitical map evolves, such statements underscore the urgent need for a continental maritime framework — one that balances national aspirations with regional stability, ensuring that the pursuit of “my ocean” becomes a collective African mission, not a cause for future wars.

source: Kenyans.co